From 1960s since today, the use of nitrogen to fertilize wheat crops has multiplied by 10 in the world, because it improves soil yield. This practice may be directly linked to the high prevalence of celiac disease, a human autoimmune condition.

Wheat fields are being fertilized with more and more nitrogen and this practice may be directly linked to the increasing prevalence of celiac disease, an autoimmune human condition. Between the 1960s and today, there has been a ten-fold increase in the use of nitrogen fertiliser for wheat crops worldwide, because it improves soil yields. Wheat grown with excess nitrogen transfers more gliadin, a group of proteins involved in the formation of gluten, to the grain and its flours. It is precisely the reaction to gluten and the difficulty humans have in absorbing it that causes the coeliac disease, a condition that is clearly on the rise in the developed world.

Between the 1960s and today, there has been a ten-fold increase in the use of nitrogen fertiliser for wheat crops worldwide, because it improves soil yields.

This is the main conclusion of the study “Could Global Intensification of Nitrogen Fertilisation Increase Immunogenic Proteins and Favour the Spread of Coeliac Pathology?” published in the journal Foods and led by Josep Peñuelas, CREAF and CSIC researcher, with the participation of CREAF researcher Jordi Sardans and specialists from the Czech Academy of Sciences (Czech Republic), the University of Antwerp (Belgium), the Pierre Simon Laplace Institute (France), the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (Austria) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing (China).

The study confirms that the per capita intake of wheat products has remained more or less constant over the last decades, although the concentration of gliadins in wheat has increased. As a consequence, the average per person consumption of gliadins has increased (approximately 1.5 kg more per year). Likewise, the study also confirms that the amount of land fertilised with nitrogen is practically the same and what has been intensified are the kg of nitrogen applied. Factors such as possible new bread additives in bread that may cause allergies and improved accuracy and efficiency in the diagnosis of coeliac disease have also been taken into account.

Nitrogen fertilisation drives to a possible direct global health problem. The relationship we have identified does not imply that there is a single direct cause: there may be other factors, although this one is important.

JOSEP PEÑUELAS, researcher at CREAF and CSIC.

“Nitrogen fertilisation drives to a possible direct global health problem,” says Josep Peñuelas, director of the research, although he insists on the need for caution when drawing conclusions and reminds us that there are few studies on the subject. “We do not carry out the medical study, but rather warn of a new consequence. The relationship we have identified does not imply the existence of a single direct cause: there may be other factors, but this one is important. He adds that “the nitrogen fertilisation that we ecologists study has very important effects on micro-organisms and the land functioning, and we add that it also has an effect on human health,” he explains.

A global health change

The impact and harms of excessive nitrogen fertilisation has been observed mainly at the environmental scale (e.g. eutrophication and acid rain), and a direct effect on human health linked to coeliac disease is also possible.

"Global change is leading to a change in global health. As ecologists we are engaged in global ecology and we are interested in working with all organisms, not only bacteria, plants, arthropods or birds, but also with humans" Josep Peñuelas

“Everything suggests that we have another risk factor caused by a world richer in nitrogen through the increase in gliadins in wheat, an important risk factor that may explain, at least in part, the increase in the prevalence of coeliac disease,” says Josep Peñuelas.

The ecologist’s interest in a health issue is explained in a forceful way: “global change is leading us to a change in global health”. And he argues that “as ecologists we are dedicated to global ecology and we are interested in working with all organisms, not only with bacteria, plants, arthropods or birds, but also with humans”.

Figure 1. The annual amount of fertilizer nitrogen applied to wheat crops globally increased by between about 10 and 100 kg between 1961 and 2010. The overall yield has increased, although it refers to a similar area of land. The direct relationship between fertilization and yield during the period 1961-2010 is only 3.5 times higher than it was 50 years ago.

A fertilizing element and an essential grain

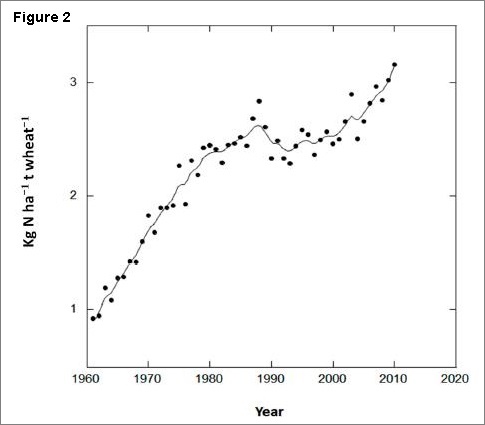

The demand and application of nitrogen fertilizers in crops around the world has increased substantially (figure 2). Data provided at the last International Conference of the Nitrogen Initiative indicates that global nitrogen fertilizer consumption increases by 33% between 2000 and 2013. FAOSTAT data from 2014 2018 indicate that frequent use of this element to improve yield of land is common throughout the world, but with regional differences: increasing from high to low, in East Asia, South Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, North America, Asia Western, North Africa and Oceania, and decreases by 1.5% in Western Europe.

Wheat is currently the most widely planted crop and continues to be the most important food grain for humans. In addition, on the one hand, the direct consumption of foods derived from wheat has decreased in some countries (such as the US) but, on the other hand, the flour used as an additive causes a net increase in the annual per capita intake of this cereal. This means that humans have increased the net gluten we eat per person from 4.1 kg in 1970 to 5.4 kg in 2000. The crops of this essential cereal in our diet now occupy an area of 217 million hectares throughout the world.

Eating gluten, a wheat protein, can trigger various intolerances and allergic diseases, among which celiac disease is the most widespread in humans. Its average prevalence in the general population of Europe and the US is approximately 1% (in the US it went from 0.2 to 1% in just 25 years). However, there are some regional differences: the prevalence of celiac disease is between 2 and 3% in Finland and Sweden, and 0.2% in Germany. Science is still careful to indicate the causes, but they are probably related to the environmental components of celiac disease, such as changes in the quantity and quality of ingested gluten, infant feeding patterns, spectrum of intestinal infections and colonization by intestinal microbiota.

Reference article:

Foods 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9111602